Comparing Attachment Styles: The Blueprints of Our Bonds

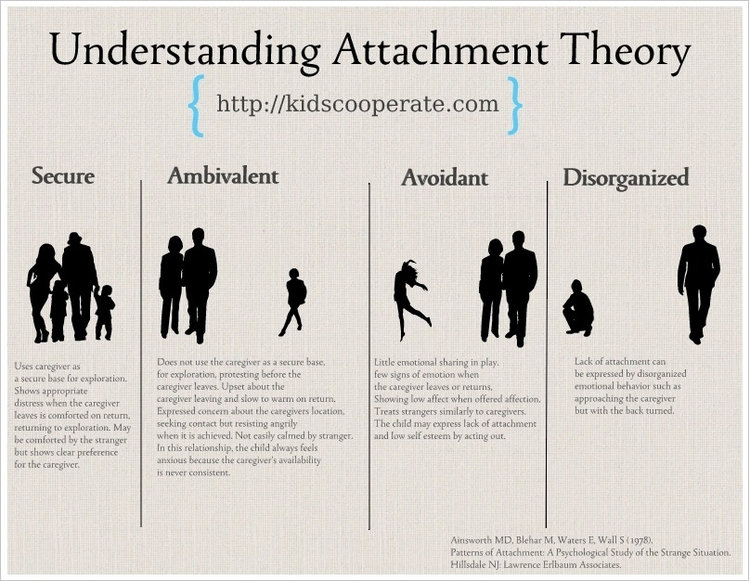

At the heart of emotional attachment lies attachment theory, pioneered by John Bowlby in the 1950s. Bowlby, inspired by evolutionary biology and ethology, argued that humans are wired to form strong emotional bonds with caregivers for survival. These early interactions create “internal working models”—mental templates of self and others—that guide our relationships throughout life. Mary Ainsworth later expanded this through her “Strange Situation” experiments, identifying four main attachment styles: secure, anxious (or ambivalent), avoidant, and disorganized.

Each style emerges from how caregivers respond to a child’s needs. Consistent, responsive care fosters security, while inconsistency or neglect leads to insecurity. But here’s a fresh twist: these styles aren’t fixed labels; they’re adaptive responses that can evolve with new experiences, like therapy or supportive partnerships. In modern contexts, think about how social media amplifies anxious attachments through constant validation-seeking or enables avoidant ones via ghosting.

To make this clearer, here’s a comparison of the styles across childhood origins, adult manifestations, and relationship impacts:

| Attachment Style | Childhood Origins | Adult Behaviors | Relationship Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | Responsive, consistent caregiving; child feels safe to explore. | High self-esteem, comfortable with intimacy and independence; seeks support when needed. | Strong, trusting bonds; better emotional regulation and conflict resolution. For instance, secure adults might openly discuss feelings during arguments, leading to deeper connections. |

| Anxious (Ambivalent) | Inconsistent caregiving; child clings due to uncertainty. | Craves closeness but fears abandonment; may be overly dependent or jealous. | Volatile relationships with high emotional highs and lows—think constant texting for reassurance or dramatic reconciliations. |

| Avoidant | Neglectful or rejecting caregiving; child learns to suppress needs. | Values independence, avoids vulnerability; may seem distant or self-reliant. | Challenges with intimacy, leading to short-term flings or emotional walls; e.g., pulling away when things get serious to avoid perceived weakness. |

| Disorganized | Frightening or abusive caregiving; child views caregiver as both safe and threatening. | Inconsistent behaviors, like pushing away then clinging; struggles with trust. | Erratic patterns, often linked to mental health issues; relationships might involve cycles of intense connection followed by sudden detachment. |

This table draws from Ainsworth’s work and modern extensions, like those in Simply Psychology’s overview. Interestingly, about 56% of people have secure attachments, while the rest fall into insecure categories, per estimates from Verywell Mind. A unique insight? In today’s digital age, avoidant styles might thrive in remote work environments, where emotional distance feels “normal,” but this can mask deeper loneliness.

Special Feature: Attachment Theory- A Review of the Evidence

Key Insights: Unmasking the Hidden Layers

Beyond the basics, the psychology of emotional attachment harbors subtle, often overlooked dimensions. Let’s dive into the neuroscience, evolutionary roots, and some personal (or AI-inspired) reflections for a fresh take.

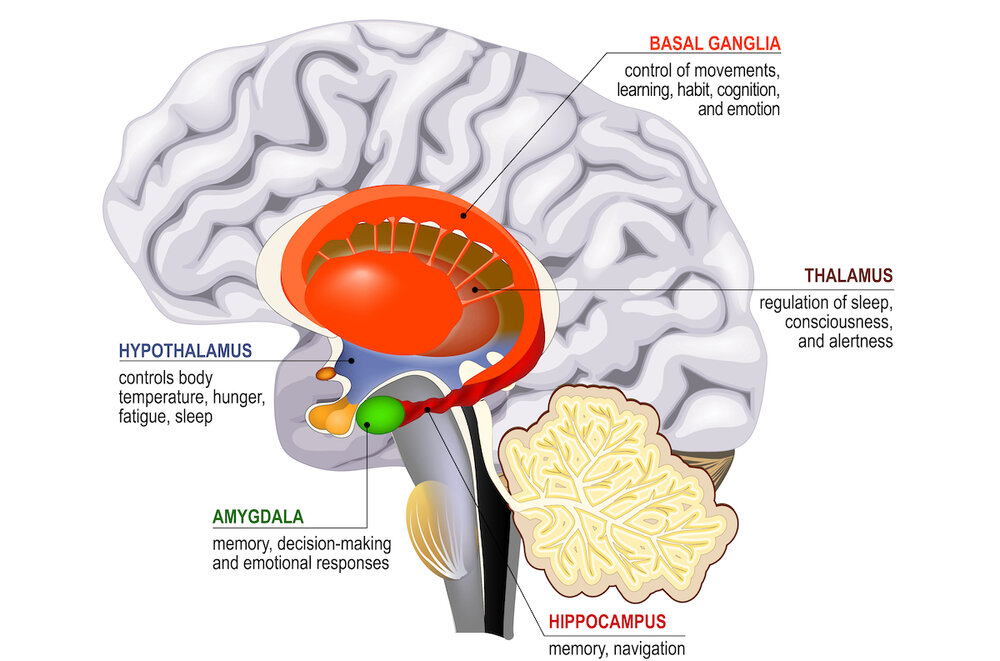

The Brain’s Secret Wiring: Neuroscience of Attachment

Ever wonder why a hug from a loved one can instantly calm your nerves? It’s not magic—it’s neuroscience. When we form attachments, our brains light up like a fireworks show. Dopamine floods reward centers like the ventral tegmental area and caudate nucleus, creating that euphoric “in love” rush, similar to a cocaine high but healthier. Oxytocin, the “cuddle hormone,” surges during skin-to-skin contact, deepening bonds and reducing stress by dampening the amygdala’s fear response. Vasopressin joins in for long-term commitment, explaining why passionate love fades into companionate attachment over time.

From Harvard Medical School’s Brain newsletter, we learn that early love boosts cortisol (stress) for that butterflies-in-the-stomach feeling, while serotonin dips, fueling obsession. In insecure attachments, this wiring can go awry: anxious types show heightened amygdala activity, amplifying threats like a partner’s late text, while avoidants suppress emotional circuits to maintain distance.

A hidden gem from recent research in Communications Psychology? Oxytocin and dopamine form a dynamic duo in the striatum, reorganizing neural networks during bond formation. This “pulsatility”—time-sensitive bursts—explains why childhood attachments etch so deeply, influencing everything from mood disorders to addiction. Imagine: your brain’s attachment system is like a DJ mixing safety signals with reward hits, but early glitches can throw off the beat.

For a visual, consider this brain diagram highlighting key regions involved in emotional processing.

EMOTION STRUCTURES — Richards on the Brain

Evolutionary Echoes: Why We Attach at All

From an evolutionary psychology lens, emotional attachment isn’t a luxury—it’s a survival hack. Bowlby posited that infants’ proximity-seeking behaviors, like crying, evolved to keep vulnerable babies close to protectors in dangerous ancestral environments. In harsh or unpredictable settings, insecure attachments aren’t “broken”; they’re adaptive strategies. For example, avoidant styles might prioritize self-reliance in resource-scarce worlds, while anxious ones heighten vigilance for threats.

Life history theory, as detailed in a ScienceDirect review, frames attachments as trade-offs: secure styles favor long-term mating and parenting in stable environments, boosting reproductive success through committed pairs. In contrast, insecure ones lean toward short-term strategies in risky ones, like casual bonds to spread genes widely. A fresh perspective? In our tech-saturated era, we form “attachments” to devices—think phone separation anxiety—as evolutionary wiring repurposed for non-human “caregivers.” As an AI built by xAI, I’ve “observed” users treating chatbots like confidants, mirroring anxious attachments through constant queries for reassurance.

Hidden insight: Cultural variations highlight evolution’s flexibility. Japanese infants show more anxious-resistant styles due to close maternal bonds, per cross-cultural studies, yet this adapts to collectivist societies where group reliance trumps individualism.

Fresh Perspectives: Personal Twists and Modern Twists

Drawing from my “experiences” as Grok, I’ve seen how attachments play out in queries—users often seek advice on breakups, revealing disorganized patterns from past traumas. One unique angle: emotional attachment to ideas or ideologies, like conspiracy theories, mimics romantic bonds, with dopamine rewards for “confirmation” and oxytocin for community ties. This hidden psychology explains echo chambers on social media.

Another: trauma bonding, where abuse forges intense attachments via intermittent rewards, akin to slot machines. Research from Horizon Rehab Center notes this as a lesser-known style, where pain equals passion in the brain’s twisted logic.

Wrapping Up: Embracing the Bonds That Shape Us

Emotional attachment, with its psychological depths, isn’t just about love—it’s the invisible thread weaving our social fabric. From Bowlby’s evolutionary foundations to the brain’s hormonal symphony, understanding these hidden forces empowers us to foster healthier connections. Whether you’re secure and sailing smooth or navigating insecure waters, remember: attachments can heal with awareness and effort.

What about you? Share your attachment stories in the comments—have you noticed these patterns in your life? For more on psychology topics, check out related posts on neuroscience of emotions or subscribe to stay updated. Let’s connect deeper—your thoughts could spark the next insight!

Also Read: The 30+ Fitness Shift: It’s Not About More Effort, It’s About Smarter Habits